Some thoughts from the bench

That’s what a comeback is. You have a starting point and you build strength and momentum from there. Stay the course, remain patient. Focus on small steps that are constantly forward. — Kara Goucher.

I knew something was wrong. I was running down from Skytop Tower in the middle of a snowstorm with only occasional animal tracks along the trail. There was an arctic wind blowing, but after climbing uphill for the past 9-miles the air felt refreshing. I had done the most challenging part, gotten to the top of the 100ft stone edifice that once served as a fire tower, taken a few selfies with the Catskill Mountains in the background, floating along the December horizon like blue and purple mounds of ice-cream. Now, I could coast all the way back down to the trailhead, in the fresh powder, the wind making the pine-boughs rise and fall, with splashes of color from red cardinals darting in and out of the trees. This was my happy place—a quiet, blustery, white-encapsulated day with no one on the trails.

Within a ½ mile of running downhill I felt my hip lock up. Or was it my leg? All I knew was that the pain in the upper quadrant of my left thigh was so intense that it became difficult to run. I tried to lean more on my right leg and change the way my foot was striking the ground in an effort to relieve the stabbing pain. Nothing worked. I had to stop, at one of the mountain gazebos, the wooden bench covered in a foot of snow, to try and stretch my hamstring. I wasn’t sure how to make it stop but I thought stretching would help and then started to manipulate my hip in different directions in an attempt to right whatever was wrong with it. I would dust the snow off and begin moving again but would only get ½ a mile or so before the pain would build to another crescendo, forcing me to stop. There was no “unlocking” it. So I walked for a few minutes but it was 5 degrees out, with wind gusts lashing at me. I was deep into a trail run wearing only lycra tights and a thin shell of a jacket with light gloves and a beanie. Hardly the appropriate gear for an 8-mile trek back to my car.

So, I kept running, or hobbling, or almost peg-legging it down the mountain. Here’s what the running brain does. It makes you think that if you can just go a little further, everything will right itself.. I even began to search for trails that went back up hill because when I went uphill my leg hurt less. Technically, I could have made my way towards a road and called someone, but that wouldn’t get me to the 18-miles I had planned. And I really wanted to reach the full 18-miles despite the fact that my left leg was not cooperating. The further I ran uphill, the better I felt. But I did recognize the basic law of gravity–what goes up, must come down. Despite these forays back up, I had to turn my body and my trajectory back towards the foothills. My gait changed to something that was slow and contorted, looking a bit Keyser Soze-like. By the end I was dragging myself and my left leg back to the car at a snail’s pace, albeit a winter-snail.

I had to coach a 3-day swim meet starting later that day and the pain escalated to the point that I was swallowing NSAIDs like Skittles, limping around the pool deck trying to put all of my weight on my right leg or lean against a ladder for some reprieve or both. When I returned home it was impossible to go up or down the stairs without a slow and cumbersome, good-leg, bad-leg, two-step shuffle with one hand on the banister for balance. I could barely put weight on my left leg. What had I done? I told people that I fell because that just made for an easier explanation. I had slipped and fallen a few times because I was running in the middle of a snowstorm that blanketed a layer of ice, but I knew those slips and spills were not the cause of this deep, throbbing pain that would wake me out of a sound sleep at night.

The last thing a runner wants to do is to stop running, or at least that’s the last thing this runner wanted to do. After the meet was over, I made an emergency visit to Justin Feldman, my favorite physical therapist as well as the only physical therapist I’d ever gone to. Not only was he an endurance athlete himself, (as well as being quirky and funny with a labradoodle that got up on the examination table with you,) but he had also never told me to stop running. I’d come to him with several different injuries or what runners call “niggles” and he would quickly identify what the cause of the issue was. He might have me scale back my running while incorporating different stretches and strengthening exercises. But he had never said, “you need to stop running.” That’s the best kind of PT in my book. Keep running, but just add in more. And what does an ultrarunner want to hear from a trained, licensed, physio? Keep running and do more!

After being examined and hobbling around his office, with his dog Toby in toe, he said “this is serious,” and instructed me to do “nothing” that I didn’t have to do for 3 weeks. He believed it was a torn muscle, possibly a hip-flexor or quad tear, both of which would need rest.

I really didn’t like that answer, but at the same time, I couldn’t even walk normally, so even I recognized that running was out of the question. Three weeks was not the end of the world and it was Christmas time with all of my kids home and I could just settle in, enjoy them, get some rest and everything would be just fine.

I limped around for two weeks and once I could manage a semi-normal walk, off I went to the trails, dragging my daughter with me. Yes, running is my favorite form of movement but in the end, the overriding desire is always to just get outside, in nature and away from the noise of industrialized life as often and as long as possible.

At one point on the walk, my daughter was so cold that she said she couldn’t feel her fingers or her toes. I was annoyed. Really? Why didn’t you layer up more? Why didn’t you wear wool socks and glove liners?

“Mom,” she said, exasperated. “Just because you can’t run doesn’t mean I have to walk with you in sub-zero temperatures for hours at a time!”

True. Very true. Sobering statement. I apologized. But I still begged her to put on warmer layers when we got home so that we could turn around and go right back out to the trails again.

When I went back to visit my PT and he asked me to move this way and that way and try to balance or jump or bend on the leg that was compromised. Any time I tried, it didn’t go well. “You need to get an MRI,” he said. “I think this could be a stress fracture. I’m not certain but after 3 weeks this should be much better if it was just a muscle tear.”

Thankfully, we live in a region where your PT and your Sports Ortho are both endurance athletes, and even more than that, they’re friends. The person he referred me to, Jay Friedman, was not only an endurance athlete and a sports ortho, but also a very accomplished ultrarunner, who I had written several articles on. Not only was I in capable, professional hands, but I was under the care of two people who did what I do and understood how hard it was to not do the thing that we loved to do.

I told him how the injury came about and even how the week prior had been plagued with some thigh and hip pain, but only on the downhills. Having learned and embraced the “do hard things” ultrarunning dictum, I had almost become too comfortable with high levels of pain. The alarm bells did not fully sound. It was only when I couldn’t physically take another step that I sensed trouble. Jay Friedman, my doctor, said that the story I was telling him was “a narrative of a stress fracture.” He said that he had a similar story where he was running up and down this one hill that we both train on. “I was doing hill repeats and I felt fine on the up hills but the minute I started running down I had this pain in my lower back that was excruciating. Turned out I had a sacral stress fracture.”

Insert some South Park screaming in my head right here, but I thought, “no. I can’t have a stress fracture.” That would take weeks and months to heal and I have a race. The Arizona Monster. A 309-mile race. It was the inaugural year. I had always wanted to be a part of an inaugural year ultra. This one would require putting lots of miles in the bank, or stashed under the bed, or in a secret compartment in the wall or even buried out back. I had to log in hundreds of miles in a few short months and I had no time for a stress fracture. But alas, the MRI was ordered, the instructions were clear. No running, no lower-body strength exercises (didn’t have to twist my arm there,) gentle walks at most. If not, Jay warned, I could be out of the running-game for months.

Of course, I went home and did what any injured runner would do, I started Googling stress fractures and then adding in more words like “running” and “female runners,” and “recovery time,” and I didn’t like any of the answers. So, what does one do when they don’t like the answers provided by the CDC or the Mayo Clinic or John’s Hopkins or any other reputable medical site? I went to Redditt. There are so many non-professionals, anecdotal opinions on Redditt that there were moments that I was certain I would require surgery with rods in my leg and the next moment question if I didn’t have some form of rare but aggressive bone cancer. Horrified by the various diagnosis I was giving to myself based off these Redditt posts, I decided to go back to the basics. The things that always make me feel a little bit better.

I walked. I wrote in my journal. I did sit-ups and push-ups and eventually found my way back to the free YouTube workout sensation, Chloe Ting, an Australian fitness personality whose two-week ab shred videos went viral during the COVID-19 pandemic. The background music was creepy, making me feel like I was in a seedy dance club in Bangkok or throwing me into pandemic flash-backs. But at least I was doing something.

Do what you can, I told myself. I knew I wasn’t going to a gym. So, I found some old dumbbells and went to work lifting those and trying to come up with some make-shift exercise routine that would at the very least, strengthen some parts of my body that running could not.

Because I couldn’t run, I found more time to walk with friends and spotted a Snowy Owl and several Hawks and many porcupines that I may not have noticed if I had been running. I took pictures of snow-covered cats’ tails and old barn windows and water that pooled and froze in staccato patterns. When I went to get the MRI and sat in the waiting room, remembered being a young college student—injured from training and running my first marathon and unable to barely walk. I was at the University of Oregon and in the trainers’ room where I saw so many athletes from football players to track runners to basketball stars and gymnasts all in this basement riding stationary bikes, being wrapped up in ice, lifting small weights or lying on a heating pad while a trainer slowly tried to manipulate their shoulders or ankles. It was the dark world of athletics. It was the injured list. For those that love to do whatever sport they do, being injured is a dark, isolating place. Often the injury is not clear-cut, nor is the path to recovery. It’s this grey area where the goal post is always moving. It’s an entirely different endurance event. One with no mile markers or obvious finish line. I thought about all of the ultrarunning influencers and inspirational personalities I enjoy on social media and how often their message is to push through the discomfort. To embrace the suck and accept that it’s going to hurt but that it’s going to be worth it. I loved all of those messages and utilized them in my mind when I ran a 100-mile race or a 250-mile race but ironically, being unable to run was so much more challenging. There were no cheerleaders or cowbells or aid-stations. There were no Instagram reels about sitting on the bench or the view from the sidelines. There were no fellow competitors to struggle along with. It was just you a receptionist, an MRI technician and the pages of US Magazine to flip through.

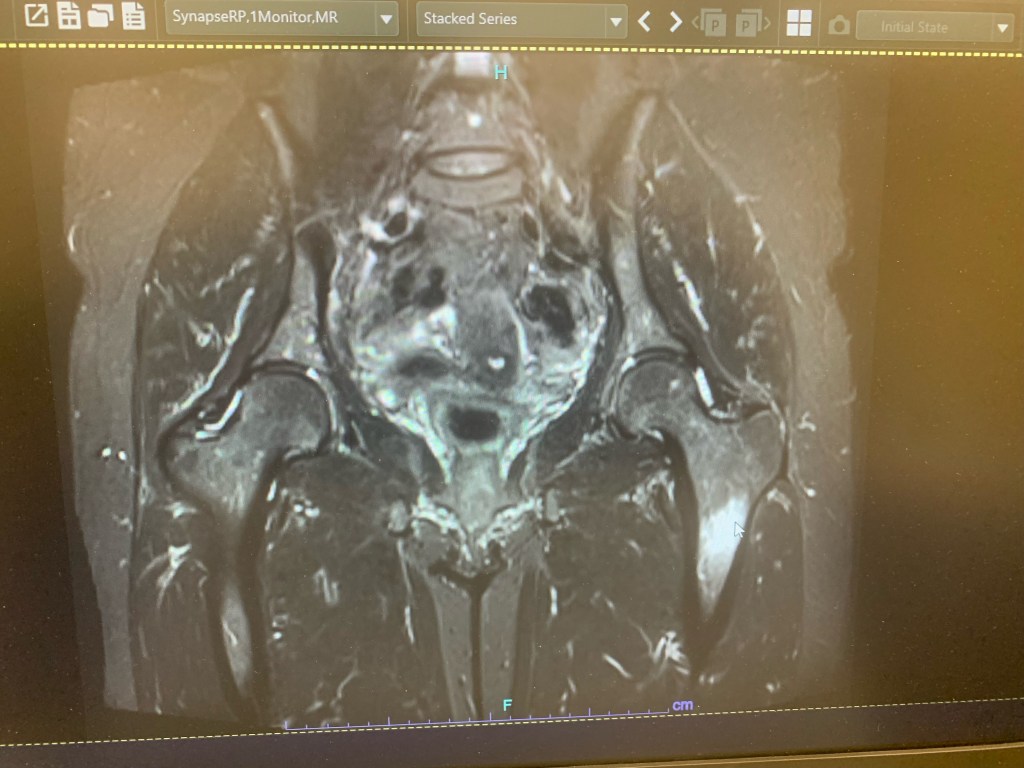

The MRI showed a Femoral stress fracture and the DXA-scan showed healthy bones. The first caused me to cancel my race, which was hard and still hurts as the start creeps closer. The second made me hopeful. So many running-critics, even those in my own family, are always warning of poor bone health. When my doctor had ordered a bone scan I was scared. What if I proved all the critics right? What if my bones were paper-thin and all about to break at any moment? Thankfully, that was not the case and my bones were strong. I had gone through three years of running thousands of miles on all kinds of trails and conditions without an injury that instead of being sad, part of me knew how lucky I had been. “I don’t like to call them over-use injuries,” my sports doc aid. “Because it implies, you’re doing something wrong. You’re not doing anything wrong; you’re just using your body to do what you love.”

Isn’t that the thing about love? When there’s that loss of it—from either a person or a place or an activity—it feels like the entire world is conspiring against you. As I spoke with the receptionist who was also waiting on an MRI to diagnose what was causing her hip pain when she ran, we empathized with one another about how hard it was to be out-of-the-game and the bitter taste of jealously we would get when we saw other people running carefree. “We’ll get back there,” I said to her. “One step at a time.”

This journey is not one any athlete wants. But it does come with the territory. If we’re going to move our bodies and test our limits and climb mountains? We’re going to be at risk of falling. Both are part of the training. Both are part of the race. I may not be showing up to a start line but yesterday, I was able to start my return-to-run program after 12 weeks of no running. It was one minute of easy jogging and five minutes of walking. There’s nothing particularly sexy about shuffling for a minute, but for me, it meant the world.

Healing is never an upward trajectory and I’m sure there will be more fits and starts on this journey than I can even know right now. But the perspective that is gained from sitting on a cold rock in the valley only makes each step up the mountain that much more rewarding. I wouldn’t choose this route, but it’s the one that I’m on. It’s the one that doesn’t get a lot of press or social media splashes but it is where many of us find ourselves at some point or at many points on the journey. As my mom always says, “do the best you can with what you have.” Right now, I have the ability to walk and for a minute or two, even run. And for that, I am grateful.

—Erin Quinn

Post Script—After not running for 9 weeks, I began Dr. Jay’s return-to-run protocol and now, almost 4 months later, I just completed my first 10-mile run. It’s not the Arizona Monster, but after not running for so long, it feels like an epic achievement. One day. One step at a time.

Leave a reply to Andrew Courtney Cancel reply