I was at Thanksgiving dinner at my mom’s house when I received a text from an athlete I coach. She had just completed the local Turkey Trot. She sent me a picture she and her sister at the finish and said how happy she was with the time she ran. I congratulated her and thought the picture was adorable and then she texted back, “it was a lot better than when I ran it 10 years ago and came in dead last!” I knew she had been nervous about entering this race but I hadn’t realized the reason why. This ten-year hiatus wasn’t about “life getting in the way,” but came from a feeling of embarrassment or shame. I felt so protective of her and started furiously texting back that I was so proud of her and that we’ve all come in dead last at one point or another, or at least the cool kids have.

I shared this story with my family as we were pulling things in and out of my mom’s oven and lighting candles and bumping into each other as we sliced pumpkin bread and poured hot cider.

“I came in dead last at the Shamrock Run in Kingston,” my mom said, “but I did it!”

“Mom, you were last on the bike in the Cape Cod S.O.S. (triathlon,)” said my daughter, Zosha.

“I certainly was,” I said. “I didn’t mind being last except the sweeper was a cop and it was stressful being followed by a police car, especially with my butt up in the air because that bike seat hurt so much!”

We were all laughing, sharing stories about coming in last or close to last and I started thinking about the ultrarunning community and how they actually celebrate the dead last status.

The person who is “DFL” often gets a special award. They also get to run through a human tunnel on their way to the finish line. There is an entire celebration at several100-mile and 200-mile races called the Golden Hour—which refers to the last remaining hour runners have to complete the course before they’re timed out.

What’s amazing and unique about the DFL tunnel or the Golden Hour is that they almost always draw a bigger crowd than the top competitors do. Let’s face it, ultrarunning is not a spectator sport. I know there’s been a big push to make it more accessible through livestreams and drones and fixed cameras at aid-stations, but basically you see people at the start line and you see them again at the finish line. They also can take a day or days to finish, making them a difficult sport to follow.

The reason, I believe, that there is so much more attention paid to watching people struggling to make it in by the time the buzzer goes off is because we can all relate to it in some way. We’ve all crawled across a finish line or a threshold at some point, whether in athletics or in our daily lives. There are times when it took everything you had to just get to the end of a really dark day or a rough work week or some internal battle that only you knew about. But what we recognize in those final finishers is that human spirit in all of us. That will to not give up and to keep going despite the obstacles and the pain. I love watching the final finishers of the New York Marathon or the Western States Endurance Run or the Hardrock 100. They’re running out of time but they’re not running out of determination and they’ve already gone such an enormous distance that I want to just cheer them on to the finish.

When I look at my own athletic career, the finish lines that have meant the most to me, are the ones where I had given everything I had. Sometimes that landed me towards the top, other times it put me squarely in the middle. There were times when it had me finishing towards the back and this one time, like my athlete, it had me coming in when all the lights had been turned off.

In a Nordic skiing competition in college, we had to compete twice. One day was skate-skiing and the next day was classic or “traditional” style. I had only been taught the skating technique in high school and had absolutely no idea how to do a classic ski race. I didn’t know what waxes to use or how to get up the hills without moving my skis from side to side. I was too terrified but too embarrassed to ask my new, and more seasoned teammates, so I just chose a wax color that looked pretty and ironed it on my skis, hoping for the best.

For that entire 10K classic ski race in Stowe, Vermont, I tripped, fell, stumbled and tried to hurl my body forward because whatever wax I used made my skis stick to the snow, rather than having them glide. When I finally arrived at the finish line, there was no one there. It was dark. It was below zero. The wind had picked up and I could see all of the other skiers in the lodge, by the fire, drinking hot cocoa and laughing with one another. Part of me wanted to just lay down in the snow, with the snot frozen to my face, frostbite setting in and call it a life. I was done.

After a few minutes of feeling humiliated I shook off the snow, unclipped my skis and made my way to the lodge. Not long after the feeling of failure had coated me like a dark shadow, I started to feel something else. A bit of pride. Yes, I had come in dead last. No, I hadn’t scored any points for my team. But I had made it to the finish line despite sticking to the snow and falling on my face over and over again. Until that point, I had never come in last in any sporting event in my life. Yet, this is the finish line I remember the most and talk about the most because it was the one that stung. I think we tend to remember the things that hurt us, that change us, that force us to grow.

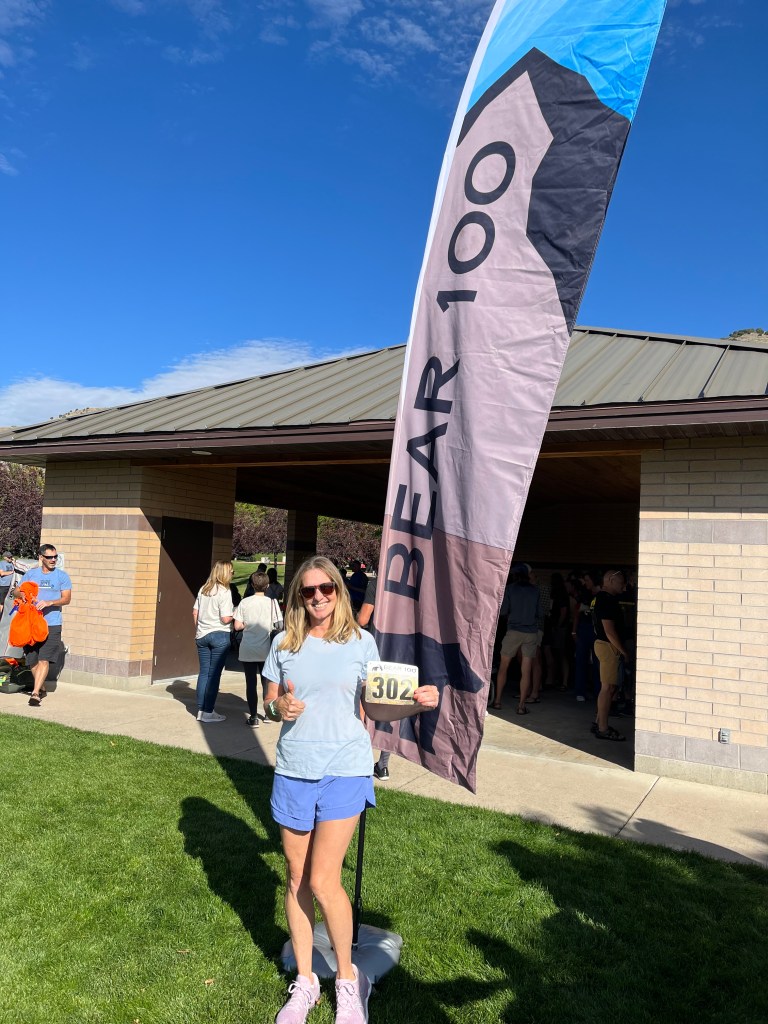

There are few things as humbling and as physically challenging as an ultramarathon with the exception of childbirth. I think the hardest one I’ve ever run was The Bear 100. Set in the beautiful but rugged Wasatch Mountain range, this race started in Logan, UT, crossed state-lines and finished in Fish Haven, Idaho on the shores of Bear Lake. Coming from the east coast, I had never run at altitude, and I had never climbed mountains that big. It climbed and descended more than 23,000ft over the 100-miles. Because of how slow I felt I was moving on the uphill I would try and run as fast as I could on the downhills to make up time. Rookie mistake. By mile 70 my quads were totally blown out. I had heard people talk about this phenomenon but had never personally experienced it. They weren’t joking. My quadricep muscles simply stopped working and I had to lean on my poles for support. If I didn’t have poles with me, (which I had packed at the last minute and had never tried to use before the race,) I think my carcass would still be out on the trail.

The poles became my legs and I fell so many times that my entire body was caked in blood and dirt. I looked like I had gotten into a brawl with a mountain lion but really, I was just in a fight with gravity and gravity was winning. I was also so nauseous that I couldn’t eat anything except for a few chunks of watermelon and although I thought I was drinking enough, I wasn’t quite in my right mind. Late I would realize that for the last 10 hours I’d only taken a few sips of my water. I was so focused on trying to move forward, so deep into the pain cave, that my only mantra was “left foot, right foot.” I would count to twenty. Once I hit twenty steps, I would bend over and try to find some oxygen in the air. I kept praying and asking God to help me stay upright. As I began the final, 7-mile descent down a technical trail with lots of scree and dirt, I began to lose peripheral vision. It was so scary. People were now beginning to pass me in a steady stream. For every 20 steps forward I went, there would be another fall, with my legs collapsing beneath me. Thankfully I had a pacer at the end, who was so patient and kind and strong that she kept helping to pick me back up. I kept repeating how grateful I was to have her with me and how beautiful the lake was and how lucky I was to have brought my poles. The more I thought about what I was grateful for, the less I thought about how much pain I was in.

When I did get to that finish line, I waved and smiled at my boyfriend who was videotaping the finish for my friends and family. I could see the clock above the finish line and realized that I was coming in with only a few minutes to spare. I was handed a belt buckle and sat down on someone’s bag chair and whispered to my boyfriend that I didn’t think I could physically make it to the car. “We’ll get you there,” he said. “You made it this far.”

I had made it 100-miles and I had no idea how. People were texting me and congratulating me and one friend who understands ultrarunning said in a group chat that I should have waited a little longer to finish because I would have gotten the “DFL” award. I didn’t know there was such a thing at the time, nor would I have waited any longer to get across that finish line and onto a chair. Another friend in that same group chat pointed out the large number of runners that started but hadn’t been able to finish. My heart hurt for them. All I kept thinking was that I had just endured one of the most challenging feats of my athletic life and how grateful I was to have finished at all, whether first or last or even after the clock had been turned off. It wasn’t how I thought the race would go, but it’s the race I was given.

Every time we step up to the starting line, it’s an act of faith. Yes, we can train and prepare to the best of our ability but we don’t know what the day or the race will give us. The Bear gave me some hard lessons but ones that I needed. Less than two weeks later I was slated to run the Moab 240, also in Utah. I believe that running The Bear ended serving as my governor in that race. It taught me not to run the descents too hard and to be patient with my body at altitude and to force myself to eat and drink even if I didn’t want to.

But it also taught me that I was capable of moving through extreme discomfort and painful places. It reinforced to me that encouraging myself in a kind voice and praying to God for assistance and focusing on what was working and what I was grateful for rather than what was not working, would help me to move forward during those dark swells.

Much like that Nordic ski race decades earlier, the Bear taught me, that there is value in coming in after the lights have been turned off. That if you made it to the finish line, even after everyone else had gone home, that you could simply stand on a podium of your own making.

I thought about my athlete and how amazing it was that she showed back up, ten years later, and gave herself a chance to do it again, this time finishing in the middle of the pack.

And I thought about all of us and how there’s that very human fear of coming in “last,” even though someone has to come in last. And how the person that does come in last, has often had to overcome something monumental just to get to the finish line. I thought about that tradition in some ultramarathons, at least the ones that I love, that encourage everyone show up for its final finishers. They showcase those victories and triumphs as much as they do the elite runners at the front of the pack. At the end of the day, we’re all running the same race, just finishing it at different times.

I believe that coming in DFL is so much better and so much braver than not starting at all. Lace up. Zip up. Show up. Be scared and do it anyway. I’ll be part of that human tunnel welcoming you in and If you end up DFL? Congratulations. Now you’re one of the cool kids.

Erin Quinn

Leave a comment